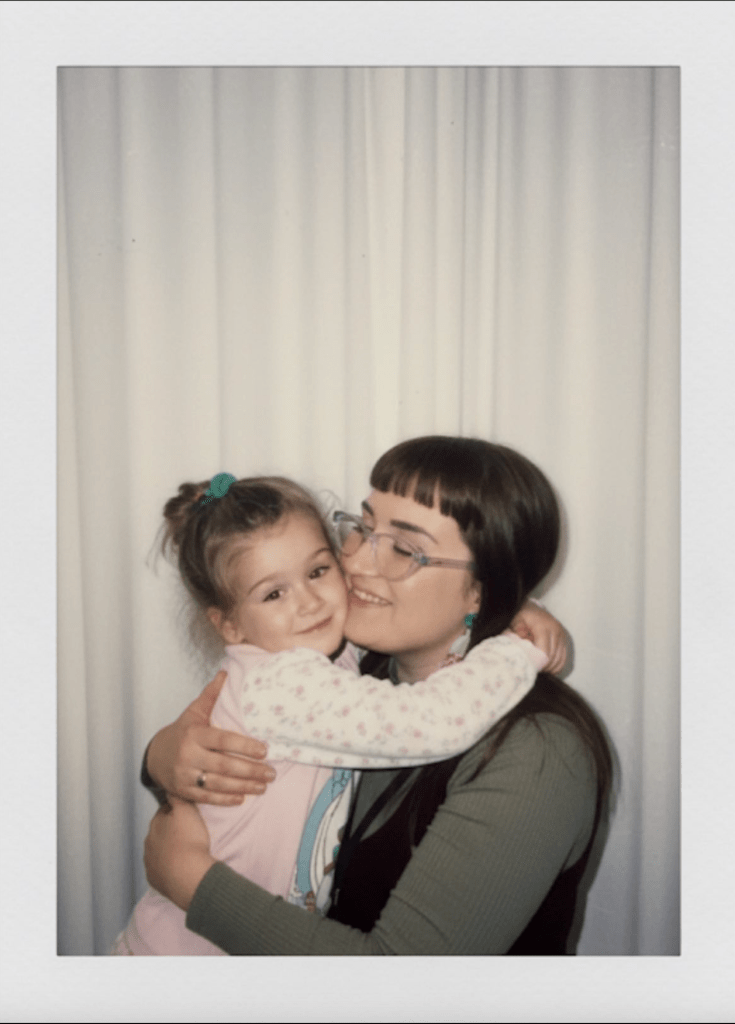

Recently I saw a nice photo in my social media feed, of my therapist colleague Sarah Harrower, in a polaroid photo, hugging a little girl, presumably at a family gathering.

Sarah’s allowed me to reprint it here. Before you scroll down, have a good look. What do you think? How old is the girl? What’s the relationship between Sarah and her? What do you think happened just before and after the photo was taken?

It’s lovely, but unremarkable really, until you know who the little girl is.

I was about to scroll past it myself when I caught the caption:

“Sometimes AI can be used for good. Here’s a generated image of me with my 4yo self. Now it’s not just in my mind that I hug me, but in my eyeballs too”

The little girl was Sarah.

What?

She had used AI to create a photo from 2 photos, uniting adult and child self for a hug, and here’s the key: believably.

No dicey photoshopping. It looked so real. Like time travel, right there.

I wasn’t the only one moved by it. The comments thread was full of hearts and teary emojis, and those combinations of words that suggest non-performative, genuine astonishment and awe.

But how much is this about the tech? Did Sarah get to hug Sarah thanks to a kind of AI Time Machine?

Well, as Sarah’s caption implies, while the latest upgrade is pretty amazing, this kind of time travel is nothing new.

She and I are trained in using imagery and visualisation to make moments of hugging your young self happen; it’s arguably a kind of time travel we can claim is very real, at least to parts of our brains.

We know that in one study the brains of pianists told to imagine playing a piece showed up the same brain activity as when they actually played it; parts of our nervous systems can’t distinguish imagination from external reality.

Caroline Burrows talks about this study in her training for Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, a WHO-endorsed treatment for trauma recovery that makes full use of our abilities to visualise in order to time travel.

The aim is to heal deep parts of our brains and bodies, parts that need to feel what time it is now. To feel the reality of the historical threat now being truly in the past.

It’s one thing to know a threat is in the past as a fact, but another to feel it as belonging to the past, as having passed into history. So we can feel safe, deeply.

That’s why horror movies work, even though we know in our clever frontal brains that it’s all fake blood, the deeper, ancient limbic brain can’t trust that reassurance, and hits the fight/flight/freeze button.

The difference between running from the cinema screaming and screaming with delight is in how much you can believe your frontal brain’s reassurances. For the deep brain, until proven otherwise, that blood is real.

We harness for good this confusion between inner and outer realities, when we look forward to something, or dine out on a good memory. The deep brain, back there in darkness, doesn’t know it’s not happening now, and some of the good feeling occurs, as if the thing is happening.

I read in a travel segment that the majority of the joy of travel is in the planning! We go there long before we go there.

And of course long after we have been there, we go back. For a lovely warm memory of travel or companionship or awe in nature, that’s great. No one comes to therapy wanting help with a beautiful waterfall they once saw.

No, they come because of the other edge of the sword of this inner-outer confusion, the pain of past and future threats being experienced now. That alone accounts for most of the mental suffering I have ever encountered, personally or as a doctor and therapist.

Read that again.

Most of our pain occurs because the deep brain doesn’t have a clock or a calendar, just a big red painful button to hit in case of emergency. If it senses threat, it’s safer to assume it’s happening now.

Your experiences of past threat that live in your memory, and your gnawing worries about future threat that live in your imagination, are treated by the deep brain and the body it’s deeply wired to, as present dangers.

It’s worth noting that this has immense value in evolutionary survival terms, as tribes of ancient humans were driven to err on the side of caution.

We are descended from the tribes that stayed on high alert after the threat had passed, and when anticipating a coming threat. We would not be here without their brains, experts in living with recurrent mortal threats.

But modern society, where most such threats are history, doesn’t recognise this. It doesn’t pay its respects to the ancestral minds and bodies. It sees our inherited capacity for painful memories and gnawing worries as emotional and irrational.

So this pours shame all over our deep brain confusion, which means we can’t bear to look at what’s going on, giving rise to so many of the chronic stress states and stress-related medical illnesses I have learned about since medical school.

Sadly little of what I learned there – taught and studied so earnestly – has helped with the underlying stress. In fact much of what I learned there too often adds to it.

What a harmful, sad misunderstanding we have made of ourselves.

And yet this double-edged sword of inner-outer confusion is so powerful! It got tribes of us through traumas untold, by allowing us to communicate pain and threat with each other, and to time travel in both directions together. To plan, to reminisce, to mourn, to hope. To create safety.

Evolution built us for security, that’s how we are still here. Still telling stories, still seeking safety together.

What is storytelling but a kind of shared time travel? And how much of our storytelling is a kind of therapy? Therapy means healing, and healing means wholeness. Healing together means becoming more whole within ourselves and our cherished groups.

Therapy is no new invention, it’s been the job of elders in Indigenous traditions for tens of milennia to hold the stories, and help others to use the confusion of their deep brains, through singing, dance and images on walls, rituals and other spiritual practices.

I can imagine – as if it is real – an elder 50,000 years ago saying to a suffering younger adult tribe member: “I wonder if you can imagine the child you were, and hold them in your lap, here on this rock, in this cave with me? Really imagine this – I will too – and it will feel real to you in some way I think”

And yet here we are in 2025 able to make images where previously we could only imagine. That young Sarah really looks like she is getting a hug from Sarah-now.

If AI can imagine something for us so well, will we lose our imaginations? Is AI a threat to the hundreds of milennia of heirloom ability to make movies in our minds long before movies were a thing?

Well, we say something like that with every technological advance. I like to think we will get our messy human paws all over it and make it our own, for better and for worse. It will be artificial for only so long before it reflects genuine human stupidity and brilliance you can’t get anywhere else in this universe as far as we know.

Plus, I look at that little girl getting that hug, and I sort of forget to think. Time bends beautifully.

Maybe some images get called timeless precisely because they harness our deep brain confusion. Seeing that hug, my deep brain gives me a warm surge of peace and contentment it’s pretty sure is happening now.

And whenever I think of this image in weeks, months or years to come, my stupid precious deep brain will let me time travel back to the first time I saw it, and feel its nowness…anew.

Thank you Sarah, for daring to care for your inner little one like this, and for daring to share the moment you made together with us.

#psychiatrying

Further reading about the neuroscience of trauma includes Dr van der Kolk’s book, and a more recent local title by trauma researcher and therapist Sarah Woodhouse, You’re Not Broken. The Blue Knot Foundation has excellent resources on trauma, as does The Australian Childhood Foundation.